By Bronwyn Barrera, MBA, and Kate Ryan, ADHA Staff

February 27, 2023

Learning was always Konnetta Putman-Sparks’ true passion, from the time she was a little girl. Born March 25, 1919, in South Carolina, Konnetta E. Putman grew up in an education-focused family.

Her father, a dedicated construction contractor, and her mother a disciplined teacher, always emphasized to the children the value of learning and the avenues to equality that education could open.

“Education was the only way to get on the same level as those doing what I wanted to do. My whole family believed wholeheartedly that the only way to try to gain equality was to be prepared.” Konnetta recounts.

Eager to Learn

Konnetta was eager and extremely bright from an early age, with dreams that would challenge the status quo and break barriers. Her family moved to Washington, D.C. where she spent her childhood, about a 30-minute walk from the Howard University campus. She often talked about pursuing higher education and studying some form of medical care. Her determination and her family’s support led her to enroll at Howard University in 1937, to pursue medicine at a time when fewer than 1.2% of black women were completing college degrees.1

She recalls that it was then that she first learned about dental hygiene.

“Part of the Howard University entrance physical was getting a dental exam on campus. I will never forget the first dental hygienist I saw. She was outstanding. She was wearing her white cap and a gown with a purple ribbon in the middle. I kept asking the dentist performing the exam ‘Who is that lady? What is she doing?’ That was the beginning of my life in dentistry.”

A Change in Plans

Konnetta Putman-Sparks, RDH, BA, MA

As is often the case with students as they explore their options in their first years of college, Konnetta changed her major to zoology. Still fascinated by the process and care in the dental hygiene courses, she became a repeat visitor to the school’s dental clinic that shared hallways with the science courses.

By her senior year, Konnetta felt that her passion lay in dental hygiene and decided that it should be her next step. After graduating with a Bachelor of Science in Zoology from Howard University in 1941, she was in search of a new adventure. A lifelong Big Ten Conference football fan, Konnetta set her sights on attending a participating university. She was accepted into several Big Ten programs, including the University of Michigan, but eventually decided that the University of Minnesota program was the right fit for her.

Overcoming Challenges through Community

The University of Minnesota had been admitting black students since the early 1880’s and she is proud of the Certificate of Dental Hygiene from U of M, but it wasn’t all a smooth ride. Upon acceptance, she learned that segregation sentiments would curb her ability to complete the clinical studies in the second year of her program. She would need to supply her own patients who were not partial to her color in order to complete her clinical work for her certification, as the program could not guarantee her a selection of willing patients. Konnetta considered switching to Michigan to avert this obstacle, but instead found encouragement from a Howard University professor who was a University of Minnesota alumnus, to stick it out and fight for her rightfully earned placement.

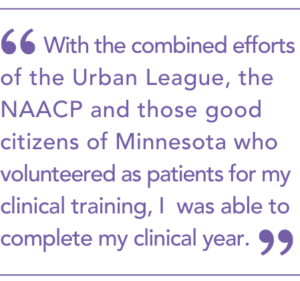

“That professor encouraged me to go to the University of Minnesota. He advised me to stay there for one year, but also to make sure I had a backup where I could transfer to if I needed. My professors at Minnesota were also concerned for me not being able to complete my second year. But with the combined efforts of the Urban League, the NAACP and those good citizens of Minnesota who volunteered as patients for my clinical training, I made it through and was able to complete my clinical year.”

After graduating in 1943, Konnetta returned to her family in Washington, D.C. to begin practicing as a dental hygienist. But the United States was 18 months deep into World War II, the dental profession among blacks was rare and segregation laws also made it difficult for her to find employment. After an extended search, she found a black dentist needing hygiene assistance and began practicing in his office and teaching her patients about oral health. For many of them, Konnetta Putman was the first dental hygienist they had ever seen or been cared for by, illuminating the early inequities in oral health care in black and brown communities.

From Clinical to Classroom to Carl

Although the clinical work was gratifying, Konnetta longed for the classroom again, this time in a teaching capacity to bring more dental hygienists into the profession. Through word of mouth, her interest reached peers at Howard University who in turn offered her a teaching position that had opened up. So, she left private practice and embarked on dental hygiene education.

Konnetta was thrilled to return to the halls that inspired her love of dental hygiene, which unbeknownst to her, would also lead her to the love of her life. Carlton A. Sparks, a WWII veteran, was enrolled at Howard University College of Dentistry. His program of study spanned the hallways where Konnetta taught, sharing time, classrooms, friends and a passion for oral health. Upon Carl’s graduation in 1948, the two married in Washington, D.C.

Konnetta at the New York City College of Technology

New York Transfer

Her teaching earned Konnetta Putman-Sparks acclaim that reached the ears of leadership at the New York City College of Technology, today called City Tech, in Brooklyn, N.Y. She was offered a position there, to build a dental hygiene program and she jumped at the chance. Initially, Konnetta commuted to Brooklyn during the week and would return home to Washington, D.C. on the weekends – a very modern career approach for the 1940’s.

“I liked to travel. I liked to move around and learn from people in different areas. The exposure helped me become a better educator and a better director. I would recommend New York City to anyone. If there is something you want to reach, New York is one of the best places to achieve it.”

She loved the city and the opportunity to inspire a new set of students. Eventually, Konnetta and Carl made a permanent move to New York. Carl opened a private practice in the Bronx and later became the Director of Dentistry at North General Hospital in East Harlem.

Setting Sights on ADHA

Joining the American Dental Hygienists’ Association was on Konnetta’s radar. In 1957, after then ADHA president March Fong Eu, RDH, MA, EdD, gave a stirring reiteration at the annual session supporting the removal of race, color and creed restrictions from all constitutions of the organization, the House of Delegates unanimously accepted the recommendation, seven years ahead of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Konnetta was thrilled at the opportunity.

“As soon as I was able to join the ADHA I did. I had been waiting for this. I started participating in activities and meeting new people in my area.”

Representation Through Leadership

Konnetta enjoyed being an active ADHA member, but for her it wasn’t enough. She saw the growth in the profession and the opportunities it would afford black women in dental hygiene, and she wanted to help lead the change through representation. In 1971, just seven years post-Civil Rights Act, Konnetta decided to run for the office of ADHA president for the 1973-1974 term.

“I’m amazed I got the support that I did. There was someone else already running who I thought was favored to win. But when the votes came in, I had been elected to the position of President of the American Dental Hygienists’ Association. I didn’t know what to think, but I knew immediately I had to set an example. I had to walk straight, watch what I did, watch what I said, and be friendly.”

- Konnetta is congratulated by Herbert M. Sussman, president of New York City Community College, on her election.

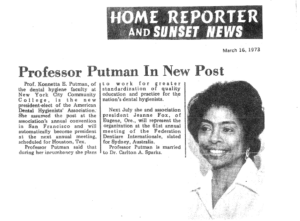

- 1973, Home Reporter and Sunset News announce Konnetta’s election win.

Konnetta and Dr. Carl Sparks at the 1973 World Dental Congress (WDC) in Sydney, Australia.

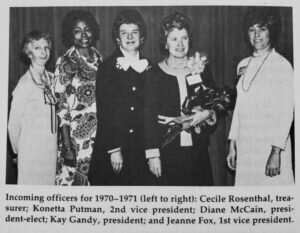

Konnetta first served as Vice President from 1972 to 1973. During this time, both she and Carl attended the World Dental Congress (WDC), the World Dental Federation’s flagship meeting in Sydney, Australia, to represent the ADHA.

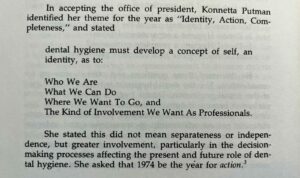

Once it was time for her to take office for the 1973-1974 term, Konnetta was ready, and became the first black president of the ADHA. It was during her term that the ADHA celebrated its 50th anniversary. Her presidential theme was “Identity, Action, Completeness, and [she] stated dental hygiene must develop a concept of self, an identity, as to: Who We Are, What We Can Do, Where We Want To Go, and The Kind of Involvement We Want As Professionals. She stated this did not mean separateness or independence, but greater involvement, particularly in the decision-making processes affecting the present and future role of dental hygiene.”2

Konnetta explains, “Our identity needed improvement. At the end of the day, you need to be able to identify yourself, identify the profession, know what it stands for and then take action based on that. We needed something to set us on that course. I wanted to give other dental hygienists a path to follow.”

- A message from Konnetta as President.

History of The American Dental Hygienists’ Association 1923 – 1982

Lifelong Learning and Legacy

Konnetta remained involved with the ADHA and the dental hygiene community long after her tenure as president. A strong believer in community involvement, philanthropy and generosity of time and spirit, she also helped found The Girl Friends Fund Inc. and led it through its legalization period. The Girl Friends Fund Inc. “brings dreams to life by providing an organization that “brings dreams to life by providing scholarships and mentoring to high-achieving, African-American students who face significant financial obstacles in their path toward a college education.”3

While teaching, Konnetta, a lifelong learner, continued to foster her own education and ultimately earned her Master of Arts in Public Health Education from New York University.

Having dedicated the better part of their lives to oral health care and education, Konnetta and Carl retired and moved to Florida permanently in 1996. They lived there peacefully together until Carl’s passing in 2008. While retired, Konnetta was frequently remembered by her former students and patients.

“You should have seen what I received for my 100th birthday. The cards, gifts, presents and well wishes from former students and colleagues were overwhelming.”

As the ADHA celebrates its 100th anniversary this year, we are delighted to be able to share Konnetta’s inspirational story and ground-breaking legacy right before her own 104th birthday! As for the next 100 years of dental hygiene, her advice to the next generation is simple:

“My motto has always been to stay involved and keep moving forward. I believe that if you honestly present who you are and what you can do, the right someone will notice. It’s always what got me where I wanted to go.”

____________________________________

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, ADHA would like to thank Mrs. Konnetta Putman-Sparks, RDH, BA, MA, for her generous time, incredibly sharp memory and enthusiasm for sharing her story of determination and courage. This noteworthy centenarian continues to reside in her coastal Florida home at the publishing of this article. She is aware of and grateful for the social media posts acknowledging and honoring her each year.

Next, for her above-and-beyond efforts to kindly connect us with her great aunt and enable us to fill in so much detail, ADHA thanks Mrs. Putman-Sparks’ niece, Ms. Konnetta King, who also shared, “There is a reason I was named after my aunt. She is remarkable and we are thrilled to finally be able to tell her story.”

Thank you also to the kind assistance of the Florida Dental Hygienists’ Association whose leadership enabled word from ADHA to get to Ms. King to help us embark on this story.

Finally, a word of gratitude to the Special Collections and Archival Collections staff at Howard University, the University of Minnesota, and New York University, as well as the leadership of The Girl Friends Fund, Inc. and New York City College of Technology for archival information and verification.

____________________________________

1 National Center for Education Statistics; U.S. Department of Educational Research and Improvement, “120 Years of American Education: A Statistical Portrait”, p.19, Table 4, https://nces.ed.gov/pubs93/93442.pdf

2 Wilma E. Motley, “History of The American Dental Hygienists’ Association 1923 – 1982”, Chicago, American Dental Hygienists’ Association, 1986, p. 282.

3 “Our Mission” The Girl Friends Fund, Inc., https://girlfriendsfund.org/about/mission/

Interview by Kate Ryan. Article by Kate Ryan and Bronwyn Barrera, MBA. Kate is a communications specialist and Bronwyn is the director in the ADHA’s Marketing & Communications Department. They can be reached at [email protected].